Ucraina/Resilienza e guerra. Parla Iryna - di Pinuccia Montanari e Giovanna Grenga

intervista a Iryna Minyailo, ricercatrice in opinione pubblica, funzionaria pubblica. Intervista in italiano e in versione inglese

Domenica, 07/12/2025 - RESILIENZA e GUERRA. La Testimonianza di Iryna Minyailo dall’Ucraina. Intervista di Pinuccia Montanari e Giovanna Grenga.

Domenica, 07/12/2025 - RESILIENZA e GUERRA. La Testimonianza di Iryna Minyailo dall’Ucraina. Intervista di Pinuccia Montanari e Giovanna Grenga.Iryna è Ricercatrice in opinione pubblica, funzionaria pubblica

Hai iniziato raccontandoci un episodio personale molto doloroso. Cosa è accaduto?

«Facevo parte di un gruppo di danza per un paio d’anni. Qualche giorno fa ho visto al telegiornale che un ragazzo di quel gruppo, che conoscevo, è stato ucciso al fronte. Non eravamo amici strettissimi, ma avevamo condiviso tempo e momenti insieme. E allora, quando mi chiedete “come stai?”, non so bene cosa rispondere. Funziono, vado avanti. Ma sullo sfondo c’è questo: la consapevolezza continua della perdita.»

Durante la nostra missione a Kharkiv abbiamo visto i cimiteri militari, e poi all’università abbiamo incontrato studenti che hanno perso compagni. È un impatto difficile da descrivere.

«Capisco perfettamente. Capisco anche l’italiano abbastanza da seguire la maggior parte di ciò che dite — l’80%, direi — perché l’ho studiato all’università. Ma parlarla è un’altra cosa, non ci sono mai arrivata davvero. I miei anni universitari vanno dal 1997 al 2004.»

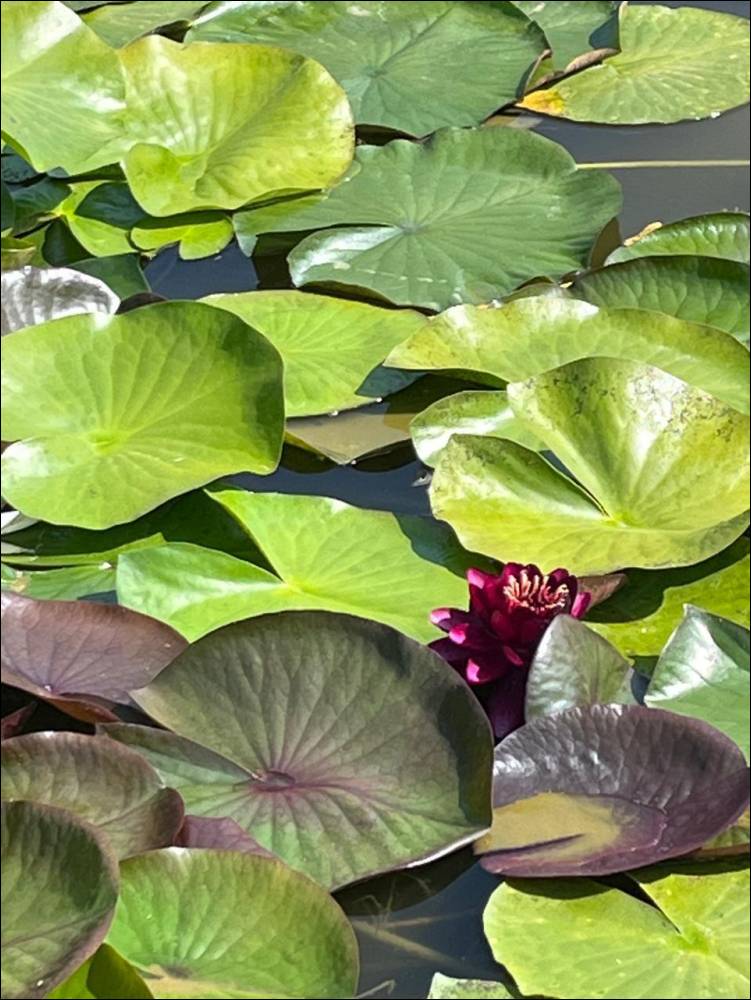

Iniziamo allora dal Giardino Botanico di Kyiv. Qual è oggi la situazione?

«In realtà avrei voluto portarvi con me stamattina. È la mia abitudine: il sabato e la domenica, prima di mezzogiorno, vado sempre al Giardino Botanico. Oggi ci sarei stata, se il telefono non fosse stato quasi scarico — per questo sono rimasta a casa. Il giardino è vivo. La gente ci va: famiglie, coppie, bambini, soprattutto nei fine settimana. Nel parco ci sono anche due monasteri, e la domenica molte persone partecipano alle funzioni. In apparenza funziona come in tempi normali. Forse notereste solo una differenza: più persone in uniforme.»

Uomini e donne?

«Le donne nelle Forze Armate ucraine, e più in generale nel settore della sicurezza, sono più numerose — in proporzione — rispetto a diversi Paesi NATO. Ma non le si vede così spesso per strada: la loro presenza è reale, ma meno visibile. Esistono, naturalmente. Ma è un quadro più complesso da cogliere con un colpo d’occhio.»

Nonostante la guerra, le aree verdi che abbiamo visto a Kyiv e Kharkiv erano curate. È sorprendente, quasi incredibile.

«Sì. C’è uno sforzo collettivo, quasi ostinato, nel mantenere una parvenza di normalità. La vita qui passa continuamente dallo stato d’allerta alla ricerca di un equilibrio. È un movimento interiore difficile: convivere con gli allarmi, con la paura, e allo stesso tempo decidere che bisogna continuare a vivere. I parchi aiutano. Sono spazi dove puoi respirare, dove i bambini possono sentirsi più tranquilli, dove le famiglie si ritrovano e condividono un frammento di normalità. Anche queste cose, in un Paese in guerra, hanno un significato diverso: normalità, serenità, quotidianità. Le parole cambiano peso.»

Una domanda inevitabile: come si concilia la cura delle aree verdi con le priorità di un Paese in guerra?

«È un nodo delicato. Le amministrazioni locali devono comunque pagare gli stipendi del personale dei parchi, dei giardinieri, degli addetti alla manutenzione. A volte capita di vedere nuove aiuole, nuovi interventi ornamentali, e spontaneamente viene da chiedersi: è il momento giusto? Perché sappiamo tutti che le risorse principali vanno alla difesa: questa è la guerra dei droni, e servono fondi per armi e tecnologia. Alcune municipalità destinano a questo scopo una parte del proprio bilancio. Non sto dicendo che il Giardino Botanico non debba essere curato. Sto dicendo che, quando lo vedo, mi chiedo sempre se le priorità siano state davvero rispettate. È una riflessione che nasce dalla vita quotidiana, non dalla teoria.»

Eppure il Giardino Botanico di Kyiv oggi è curato.

«Sì. Dopo i primi mesi del 2022, quando c’è stato il momento più critico della Battaglia di Kyiv e il giardino è rimasto chiuso e non curato per un periodo relativamente breve, è stato riaperto e ripristinato completamente. Oggi è tenuto benissimo: non si direbbe che ci sia stato un periodo di abbandono. C’è però qualcosa di nuovo: gli alberi commemorativi. Diversi alberi portano il nome di soldati caduti. E lungo il viale principale sono state installate opere d’arte a tema bellico e memoriale. Sono molto visibili. Personalmente non le amo, le trovo retoriche, ma sono parte del paesaggio di oggi.»

PARTE SECONDA

PARTE SECONDA“Curare il verde in un Paese in guerra significa custodire la vita”

Tu hai vissuto il ritorno a Kiev nel marzo 2022, dopo le prime settimane della guerra. Che cosa ricorda del Giardino Botanico in quel periodo?

«Sono rientrata a metà marzo 2022. Il Giardino Botanico era stato chiuso durante la Battaglia di Kiev, ma la chiusura è durata pochi mesi. A maggio-giugno ha riaperto al pubblico. Ricordo la cura con cui fu restituito alla città: nessuno avrebbe potuto immaginare che fosse rimasto chiuso. Kiev è famosa per i suoi viali di lillà, che fioriscono all’inizio di maggio, ed era importante che il giardino fosse di nuovo accessibile proprio in quel momento.»

Oggi com’è la situazione del giardino?

«È ben curato. Non direi che la guerra abbia lasciato segni visibili nella gestione del verde. La vera novità è la presenza di alberi commemorativi dedicati ai soldati caduti. E alcune opere d’arte poste in punti centrali del parco: installazioni simboliche, legate alla memoria e alla sofferenza. Personalmente non mi piacciono, ma testimoniano ciò che abbiamo vissuto.»

Anche altri parchi della città sono mantenuti con attenzione?

«Sì. Penso ad esempio al Parco Mariinsky, vicino al Parlamento. Anche lì la manutenzione è buona. A volte ci sono discussioni pubbliche: qualcuno si chiede se sia opportuno investire in aiuole o abbellimenti mentre gran parte del bilancio serve per la difesa. Io stessa, quando vedo una nuova aiuola, mi domando se sia davvero il momento giusto.»

Una questione quindi di priorità?

«Esatto. L’economia di guerra impone scelte durissime. I fondi pubblici vanno soprattutto alla difesa, ai droni, a ciò che è urgente. La cura del verde non scompare, ma può apparire meno omogenea. Tuttavia i parchi sono ancora curati: è una forma di resistenza civile, un messaggio alla popolazione.»

Cosa significa mantenere il verde in un Paese in guerra?

«Significa permettere alle persone di respirare normalità in un contesto che normale non è più. Dopo mesi di allarmi e ansia continua, il parco diventa uno spazio dove ricordarsi che la vita esiste ancora. È fondamentale soprattutto per i bambini: devono avere luoghi in cui sentirsi sicuri, tranquilli. Le parole “normalità” e “serenità” cambiano significato in guerra, ma i parchi aiutano a non perderle del tutto.»

Visitando l’Ucraina, molti raccontano di essersi resi conto davvero di cosa significhi vivere in guerra. Tu come rispondi ?

«È così. Le restrizioni, i pericoli, le interruzioni della vita quotidiana non si comprendono dall’esterno. Ma l’impegno nel mantenere una parvenza di vita ordinaria è enorme. I parchi, il verde, gli spazi pubblici: tutto questo non è estetica, è sostegno psicologico. È il modo in cui cerchiamo di restare umani.»

PARTE TERZA

PARTE TERZAResilienza e guerra: la testimonianza di Irina dall’Ucraina

Tra esilio, pressioni sociali e responsabilità familiari, una donna racconta la vita sotto l’invasione russa e il ruolo cruciale dell’Europa nel sostenere l’Ucraina. Irina è una donna ucraina, madre, ricercatrice, testimone diretta della guerra. In questa intervista racconta la fuga della figlia, le sfide quotidiane delle donne in un paese in conflitto, le pressioni sociali legate alla maternità e la necessità di un sostegno deciso da parte dell’Europa. Senza retorica, con lucidità e profondità, ci guida nel comprendere cosa significhi vivere e sopravvivere in tempi di guerra.

Ci puoi parlare di tua figlia e del suo percorso educativo durante la guerra?

«Mia figlia è stata evacuata in Lituania nel marzo 2022, perché il mio ex-marito vive lì con la sua nuova famiglia. Ha completato la scuola superiore in lituano, ma fin da piccola ha avuto una grande passione per le lingue. Ha studiato greco online per un anno e ora frequenta una scuola di lingua ad Atene, anno preparatorio per ottenere la certificazione necessaria ad accedere all’università. Non è ancora università, ma è un passo fondamentale. Parla già ucraino, lituano, inglese e quasi perfettamente greco. Leggere e pronunciare il greco è complesso, perché l’alfabeto è molto diverso dalle lingue slave, eppure la passione per lo studio l’ha guidata.»

Come la guerra ha cambiato la vita delle donne in Ucraina?

«Il lavoro di cura è aumentato, il divario salariale si è ampliato e la povertà colpisce le donne in misura maggiore. A livello personale, la mia famiglia si è disgregata: mia figlia ha dovuto lasciare la casa tre anni prima del previsto, evacuata per motivi di sicurezza. Abbiamo discusso a lungo, ma abbiamo deciso che l’istruzione era prioritaria.»

C’è pressione sulle donne in questo contesto?

«Sì. La guerra mette pressione sia sugli uomini sia sulle donne. Il mio ex-compagno voleva avere figli subito. C’è una pressione esistenziale: sembra che non ci saranno tempi migliori, quindi bisogna agire ora. La società spinge le donne a garantire la continuità della comunità, e questo è un peso enorme, ma è anche un istinto di sopravvivenza. Le donne portano gran parte del carico, ma lo fanno anche per proteggere la vita, garantire un futuro ai bambini e mantenere un senso di normalità, anche in un contesto che normale non è.»

Come vedi il ruolo dell’Europa nel sostegno all’Ucraina?

«L’Europa è indispensabile. Non possiamo sopravvivere senza il sostegno dei Paesi europei. L’Ucraina è la barriera tra la democrazia europea e la volontà russa di distruggerla. Putin scherza persino sull’idea di conquistare Lisbona, ma il pericolo è reale. Gli europei devono capire le vere intenzioni della Russia, che usa il soft power per destabilizzare e provocare. Ora più che mai è il momento di un sostegno deciso: le prossime settimane e mesi saranno un punto di svolta cruciale.»

E sul piano di pace proposto da Trump?

«Non possiamo accettare una pace alle condizioni di Putin. Alcune fonti indicano che il piano originario di 28 punti fosse in realtà un piano russo mascherato da proposta americana. La pace deve essere giusta e sostenibile: se non garantiamo la sovranità ucraina e la possibilità di autodeterminazione, tra una generazione o forse prima rischieremo di ripetere la guerra. La giustizia deve essere rispettata, altrimenti tutto sarà vano.»

Qual è il messaggio principale che vorresti dare alle donne italiane che ti ascoltano?

«Non si tratta di proteggere le donne da pressioni riproduttive. Si tratta di far capire quanto pesi la guerra su una società intera. Le decisioni personali e familiari sono condizionate da un contesto esterno violento. Bisogna distinguere la cultura russa dall’aggressione politica: spesso la cultura viene usata come soft power per mascherare l’invasione. E nonostante tutto, la resilienza quotidiana continua: istruzione, protezione e momenti di normalità per i bambini sono gesti che mantengono viva la società.»

English version

First part

So, I understand you’ve been involved in a dancing group for a few years. I also heard about a recent tragic news event. Could you tell me more about it?

«Yes, I’ve been in a dancing group for a few years. Unfortunately, I saw on the news that a friend of mine from the group was killed in action. He wasn’t a very close friend, but we spent some time together, you know? So when you ask me how I’m doing... I’m not sure. I’m still functioning, [Pauses]»

During our mission in Kharkiv, we visited the military cemetery there, and it was heartbreaking to see so many young people, so many lives lost. We also visited one of the universities in Kharkiv and learned how many students had fallen during the war. It was overwhelming.

«That must have been a very moving experience.»

You mentioned understanding some Italian—did you study it at university?

«Yes, I studied Italian during my university years, but I didn’t get to a level where I could speak fluently. I can still understand some, though. My university years were from 1997 to 2004. That’s a good span of time. I started my university studies after the USSR dissolved. I have experience in monitoring and evaluation of technical development.»

So, what’s the current situation at the Kyiv Botanical Garden?

«Actually, I was planning to visit the botanical garden today, since I usually go there on Saturdays or Sundays before noon. But I realized my phone wasn’t charged enough to do the interview there, so I stayed home instead. Yes, the botanical garden is still open. People are still going there. There’s a monastery church in the garden, and on Sundays, many people attend services. Families with children, couples, you see a lot of people, especially on weekends. The garden is functioning like it would in normal times, though you might notice more people in military uniforms.»

So it’s still very much a place for relaxation and reflection, but with the added presence of military personnel?

«Exactly. You’ll see both men and women in military uniforms. The presence of women in the military is higher in Ukraine than in NATO countries, although it’s still not as visible on the streets. It’s proportional to the overall share of women in the armed forces, but it’s still not as prominent.»

So, there are definitely women in higher ranks within the military, but it’s not something you see often in public spaces?

«Yes, that’s right. There are women in high ranks, especially in institutions like the UN, but you don’t see them as frequently in the streets or public places.»

What do you think is the most important thing to focus on as we move forward in the current situation?

«[Pauses] I think it’s crucial that we continue to support those who are working on the ground—whether it’s the military, humanitarian aid workers, or civilians. We need to focus on resilience, on rebuilding, and on making sure people have the resources they need to carry on. It's easy to get caught up in the politics, but we need to stay grounded in the everyday struggles that people face.»

Absolutely. Thank you so much Iryna. This has been a very insightful conversation.

«Thank you for understanding my perspective and for allowing me to share. I appreciate it.»

.jpg) Second part

Second partI must mention that Pinuccia Montanari is not only a lawyer but also a professional journalist. She was responsible for managing green spaces in two major Italian cities—Genoa and Rome. She did an incredible job developing green areas in these cities, which I think is worth mentioning because it gives you a sense of the level of expertise and interest she brings to the topic. She may not say it herself, but I think it’s important to highlight.

«That’s really impressive! Now, I know you wanted to share your thoughts on the Kyiv Botanical Garden, so let’s start with that.»

Could you tell us about your experience with it in 2022?

«Certainly. I remember visiting the botanical garden in Kyiv in 2022. I had left Kyiv for about four weeks, and I came back in the middle of March 2022. During that period, the botanical garden was closed to the public, as you can imagine, due to the situation with the war. However, it reopened in May or June of 2022, which was a great relief.»

That’s a significant reopening. What makes the Kyiv Botanical Garden special?

«The Kyiv Botanical Garden is famous for its beautiful lilac alleys. The lilacs bloom in early May, and they’re truly iconic. So the reopening in late spring was strategic because it coincided with the bloom, which is one of the highlights of the garden. After the garden reopened, it was incredibly well-maintained. Despite the difficult circumstances, you wouldn’t have noticed any lack of care; it was as if the garden hadn’t missed a beat.»

That’s wonderful to hear. So, the garden was closed for a short time during the Battle of Kyiv, but it was reopened soon after. How has the garden changed since the war began?

«Yes, exactly. The garden was closed for just a few months, and during the summer of 2022, the care and maintenance resumed as usual. There are now commemorative trees in the garden dedicated to fallen soldiers, which is a new addition. There’s also artwork in prominent places in the garden that symbolizes suffering and resilience.»

You mentioned the commemorative trees. Could you elaborate on that?

«Yes, the commemorative trees are dedicated to soldiers who have fallen during the war. There are plaques with their names on them. It’s a very moving addition to the garden. There's also an artwork installed on the main alley, which is meant to symbolize suffering. Personally, I’m not a fan of the art piece—it’s quite metaphorical—but it’s in a very visible spot.»

So, while the garden is now a place of beauty, it also carries the weight of the ongoing conflict through these memorials and artworks. Are there other green areas in Kyiv that are similarly maintained?

«Yes, there are other green spaces in Kyiv, including the Mariinsky Park, which is located near the parliament. I actually have an office near there, and from my window, I can see the park. It’s well-maintained, and it’s another example of how the city is trying to keep these areas functional despite the ongoing situation. However, there are often public discussions about priorities—whether funds should go into beautifying the city or be allocated elsewhere.»

That’s an interesting point. Given the current circumstances, how do you feel about spending funds on green spaces?

«It’s a complex issue. On one hand, I personally believe in the importance of maintaining green spaces, including trees and plants. On the other hand, I understand that there’s a war going on, and funds are limited. Some of the municipal budget is being allocated to defense, like funding for drones and military equipment, which is essential. So, while I love seeing new flower beds and parks, I also think about the larger priorities, like defense and security.»

Il seems like a balancing act between maintaining the ciy's green spaces and ensuring that the defense efforts are adequately funded.

«Exactly. It’s all about priorities. When I see a new flower bed being planted, I sometimes wonder if that’s the best use of resources right now. But at the same time, I know that maintaining green spaces is important for the well-being of the city’s residents. It’s a difficult decision, and sometimes we don’t have the luxury of perfect solutions.»

I can understand that tension. And despite these challenges, it’s clear that people in Kyiv are making efforts to preserve a sense of normalcy. How important do you think that is for the people living through this conflict?

«It’s incredibly important. Even in a country at war, trying to maintain some semblance of normal life is crucial. Children, for example, need safe spaces where they can relax and feel comfortable. Public parks and green spaces are an essential part of that. These places offer moments of peace and normalcy, which can be a respite from the constant anxiety of living in a war zone.»

That’s a very powerful point. Despite the war, the preservation of these spaces is vital for the mental and emotional well-being of the population.

«Exactly. It’s about finding moments of calm and normalcy amid the chaos. It’s not easy, but these spaces, these small acts of normal life, help people cope with the ongoing conflict.»

Before we conclude, is there anything else you’d like to add about your experience or your perspective on the situation in Ukraine?

«I just want to emphasize that even in times of war, people strive to maintain a sense of normalcy. That’s why it’s so important to support both the humanitarian and cultural aspects of life, even as we focus on defense and survival. The resilience of the people here is truly remarkable. A Personal Reflection on War, Family, and Women's Struggles in Ukraine.»

Iryna, thank you for joining us today. Let's start with something personal—how is your daughter doing? I understand she’s studying Greek in Greece now?

«Yes, that’s correct. My daughter was evacuated to Lithuania because my ex-husband is living there with his new family. She left Ukraine in March 2022. She finished her school years in Lithuania, studying in Lithuanian, which she adapted to quite well. Afterward, we decided she should pursue higher education, and that brought us to Greece. Before coming there, she studied Greek online for a year. Now, she is enrolled in a language school in Athens. This year is a foundational year for obtaining a language certification, which will allow her to enter university later.»

Wow, that’s quite an impressive journey. What languages does she speak now?

«She speaks Ukrainian, Lithuanian, English, and, of course, Greek—almost. She's still learning Greek, but she’s teaching me some phrases! It’s amazing how quickly she has picked up new languages.»

That’s impressive! Greek must be quite different from Ukrainian, though. Do you find any similarities between them?

«Actually, no. I know Ukrainian and can read and write it, but Greek is much harder for me to read. There are some similarities between the Cyrillic alphabet and the Greek one, but the sounds are so different. It's not an easy language to learn.»

Now, let's talk about something heavier. The war has obviously affected all aspects of life in Ukraine, including the lives of women. How would you say the situation has changed for women since the invasion began?

«The situation for women has definitely worsened in many ways. The amount of care work has increased, for example. Women are doing more, and unfortunately, the gender gap has also widened. Poverty rates have hit women harder. There are studies that show these trends, which are widely available, and the data is quite alarming.»

On a personal level, how has the war affected you and your family?

« ….my family has been dismantled in ways I never expected. My daughter had to leave home at 14, much earlier than I ever imagined. The war forced her to move to Lithuania for safety, and at that time, I couldn’t afford to wait for a "better time" to make decisions. It was about survival and making sure she had a good education. It was tough, but we adapted. And then, my partner and I split up. The war, the constant uncertainty, put immense pressure on us, especially on him. He wanted children, and with the looming threat of war, it became an existential issue for him. He ended up leaving to start a family with someone younger, someone he could have children with.»

That’s a very emotional experience to share Iryna. How would you say this pressure to have children, especially in a time of war, affects the women of Ukraine?

«It's a strange, almost existential pressure. I see a lot of women around me facing pressure, both from society and from their partners, to have children. Society, in a way, expects it, because there's this belief that the only way for Ukraine to survive as a nation is through reproduction. It's a survival instinct, but it’s also a very heavy burden on women. The war has made everything feel urgent, and for many men, that urgency translates into the desire to have children before it’s too late. There’s a real existential pressure to keep the country’s population up, especially with the deaths of so many men. The future of Ukraine seems uncertain, and there’s this idea that having children is almost a patriotic duty. It's very painful to watch, but at the same time, it’s part of the survival instinct of society.»

.jpg) That’s a powerful observation. So, there is this underlying societal pressure, not only on women but also on men, to “carry on” in a way. Does this affect how people approach relationships and family life?

That’s a powerful observation. So, there is this underlying societal pressure, not only on women but also on men, to “carry on” in a way. Does this affect how people approach relationships and family life?«Yes, absolutely. It changes everything. Many of my friends have been pushed to have children, even if it’s not something they were necessarily ready for. It’s not just about family planning anymore; it’s about survival. Some men feel like they won’t have another chance to have children, so they push for it, and it creates a lot of tension. I think everyone feels the weight of it—women, men, society as a whole. It's an uncomfortable situation, but it's the reality right now.»

That’s a tough situation to be in. Moving on to another topic—how do you feel about the role of Europe in all this? What do you think the European Union and European countries should do in this context?

«Europe’s support is crucial. Without it, Ukraine wouldn’t survive. If Russia conquers Ukraine, it doesn’t just stop there. Poland and Lithuania would be next, and then who knows where it would end? Putin has openly mocked the idea of conquering more European cities. Europe needs to recognize that this is a battle for democracy itself. We are the first line of defense against a regime that wants to destroy democracy, and Europe has to support us fully, not just in words but in action.»

And what about Trump’s peace plan? What are your thoughts on it?

«Honestly, I don’t believe in it. I’ve seen reports that Trump’s peace proposal was essentially just a Russian plan dressed up as a peace initiative. It’s dangerous to think we could end this war on Putin’s terms. If Europe or America tries to push for a peace settlement that involves concessions to Russia, it won’t be sustainable. The war will just restart in a few years, maybe sooner. We need a just and lasting peace—one that guarantees Ukrainian sovereignty and respects our right to self-determination.»

So, you believe it’s crucial for Ukraine to preserve its sovereignty and not accept peace on Russia’s terms?

«Absolutely. The war is not just about land; it’s about survival. If Ukraine loses its sovereignty, we lose our identity, our culture, and everything we stand for. This is an attack on international law, and it’s something the world must recognize. European countries need to continue supporting Ukraine strongly; this is a turning point. We can’t afford to back down now. The next few months will decide everything.»

Thank you so much, Irina, for sharing your thoughts with us. It’s not easy to speak about these issues, but your insights are invaluable.

«It’s my pleasure. I know my thoughts are complex and maybe hard to digest, but it’s important for people to understand the depth of the situation. We need to move beyond illusions and really see what’s happening.»

We appreciate your courage and honesty. Before we finish, could you share a photo of yourself or the botanical garden, if you have one, for the article?

«I can share some photos of the botanical garden, though not from this season. Thank you for your time. It’s been an honor speaking with you.»

©2019 - NoiDonne - Iscrizione ROC n.33421 del 23 /09/ 2019 - P.IVA 00878931005

Privacy Policy - Cookie Policy | Creazione Siti Internet WebDimension®

Privacy Policy - Cookie Policy | Creazione Siti Internet WebDimension®

Lascia un Commento